In commodity markets it seems widely accepted that market deficits are price bullish and market surpluses price bearish. Intuitively this feels right. A deficit is when demand is higher than supply and inventories (stocks) are falling. Such a situation cannot go on forever, as stocks are not infinite. Ultimately demand has to fall or supply has to rise, and in the absence of other factors (recession, technology etc) the way this happens is via a rising commodity price.

In practice it is not so clear cut, and the easier it is to hoard the commodity, the less clear cut it gets. For metals, and particularly precious metals, where hoarding is not only easy but often desirable, the picture is very muddy indeed.

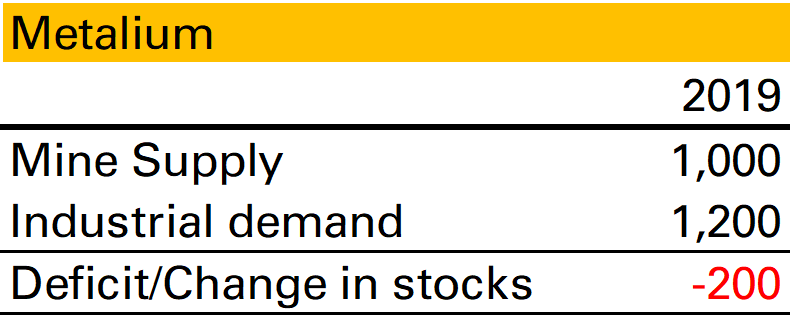

Take this S&D for Metalium, a made-up industrial metal. In 2019 1,000 units were supplied by mines, 1,200 were demanded by industry. This makes a deficit of 200, or put another way, a fall in stocks of 200. If I asked you what happened to the price in 2019 you would probably assume it moved higher.

But what if I then told you that actually what happened was industrial users midway through 2019 saw that 2020 was set to be a very bad year for demand and decided to reduce their stocks by 200?

This now seems bearish! Most likely those 200 units flooded the market, pushed the price lower, boosting industrial demand and reduced mine supply.

In other words whether a deficit is bullish or bearish can depend on the reason stocks are falling.

In base metals, where stocks are mostly held within industry and are relatively stable, this latter scenario might not be that common. But in precious metals it happens all the time, as the stockholders are not industrialists but investors. If in an otherwise balanced market a very large investor decides the future of platinum is bleak and sells their holdings of 1 Moz, the market will be in a 1 Moz deficit but the platinum price will be a lot lower.

So on a static snapshot, market deficits are not necessarily bullish. But maybe we can at least say that they imply a higher future price? After all as we noted at the beginning of this piece, stocks are not infinite. A deficit might reflect a bearish investor throwing in the towel, but they can’t keep throwing in the towel. Ultimately there will come a point when there are no more stocks (or no-one wants to sell their stocks) and the commodity price will have to rise to bring supply and demand back in line.

This is more justifiable, though still not always true. Consider these two scenarios:

- The industrialists or investors are right in their pessimism, and so a deficit in one year is followed by weaker demand or higher supply in the following year. In this scenario prices don’t have to adjust upwards.

- The sale of stock is, in itself, new information that changes perceptions. An example would be if a European central bank announced, out of the blue, it had plans to sell gold.

Finally, for gold, where almost all demand is stockbuilding (by investors, but also by people in the form of jewellery) deficits and surpluses are even less well defined. I’ll have more to say about that in another post.