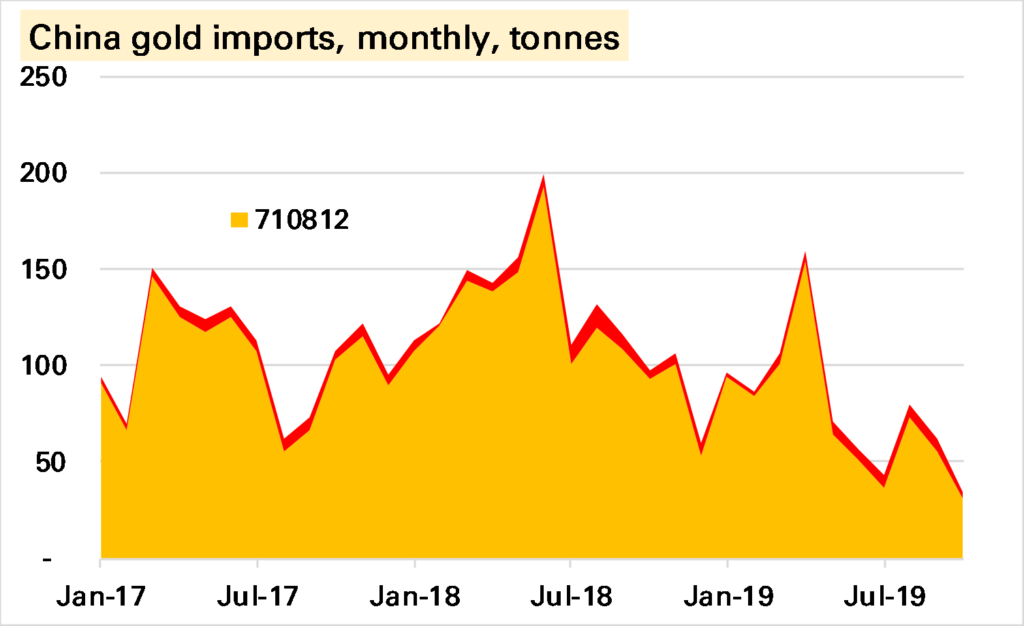

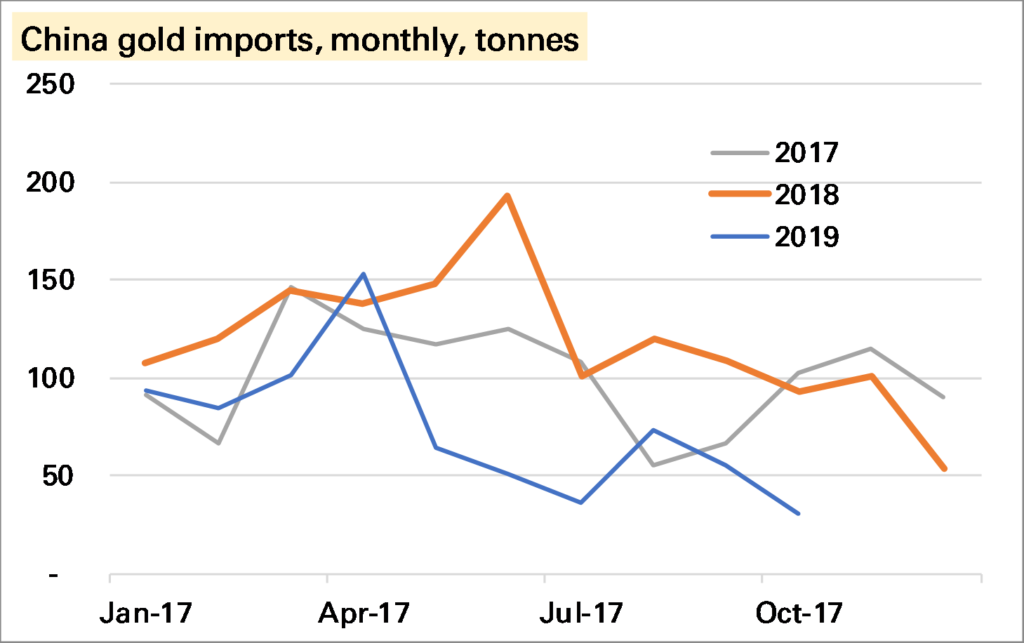

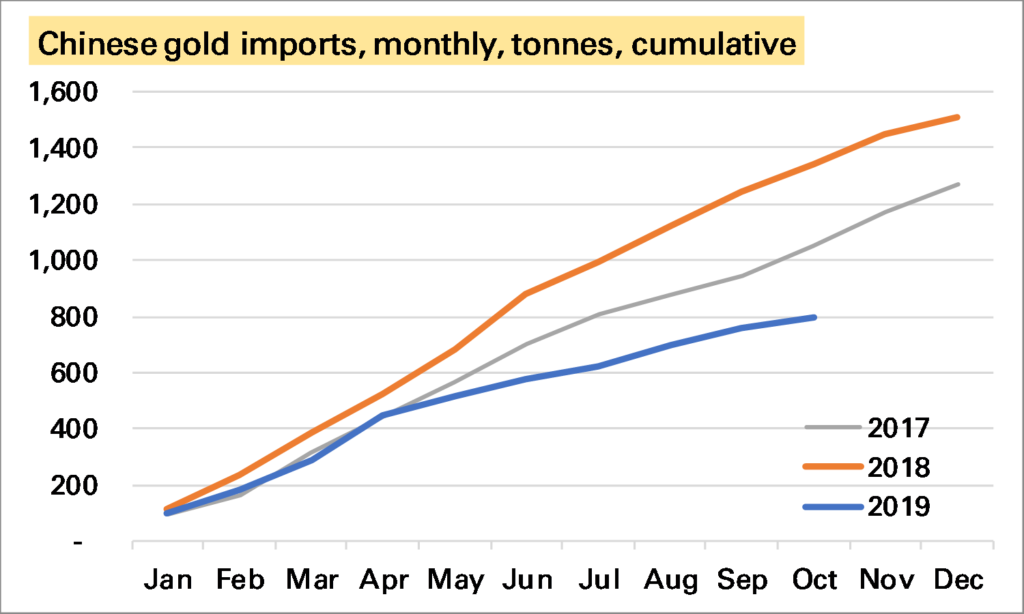

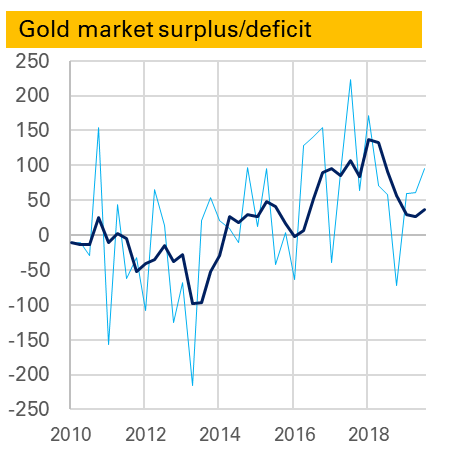

China imported just 35t of gold in October, the lowest monthly amount since it began reporting official trade data from January 2017. Seasonality must have played a role given holidays in October. But while the trajectory of imports looks a little similar to 2018, it is at a far lower level.

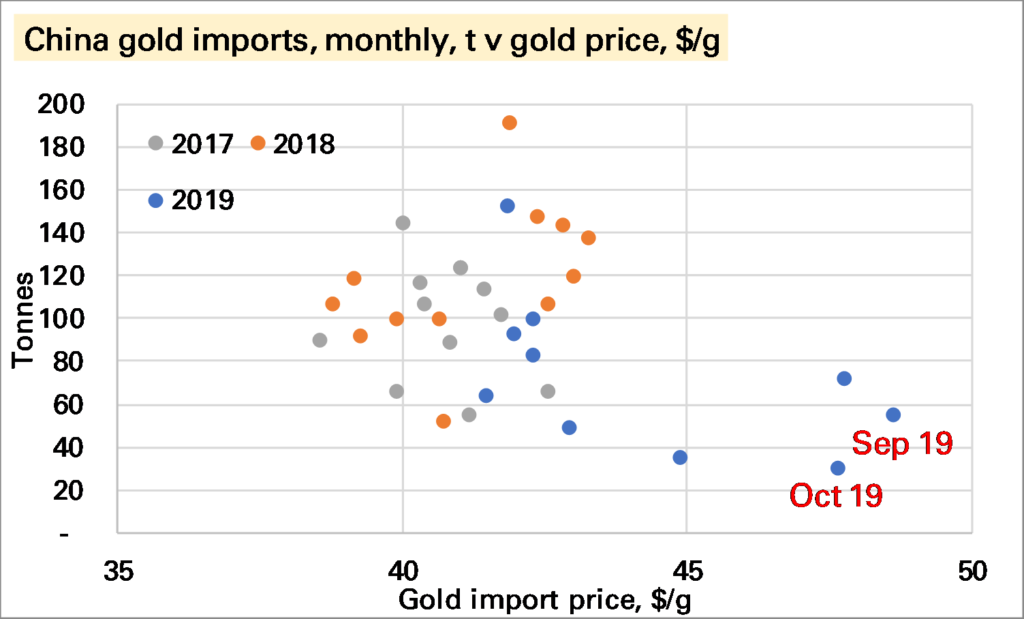

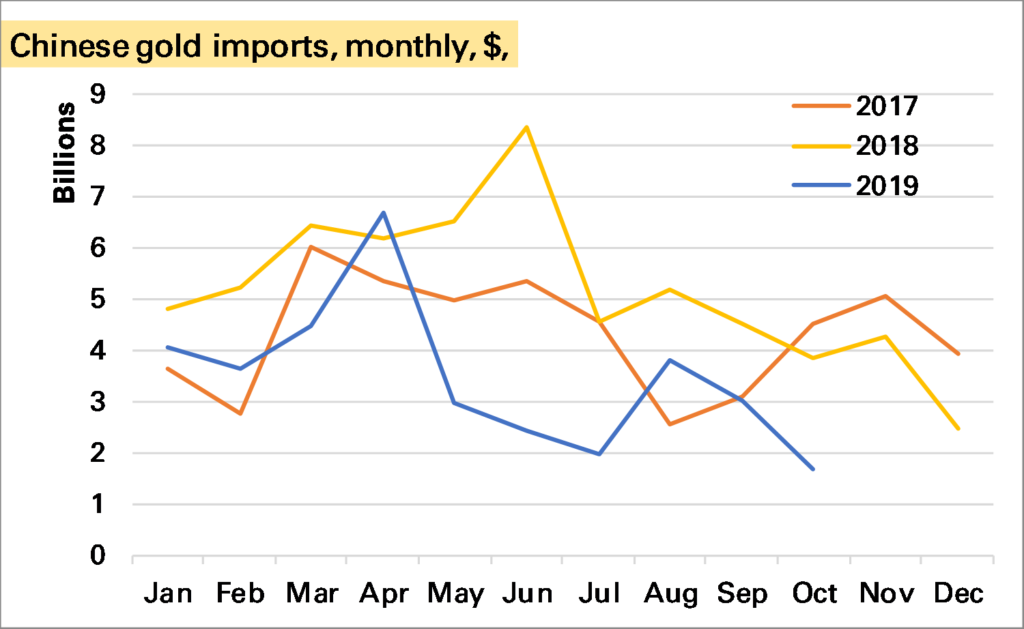

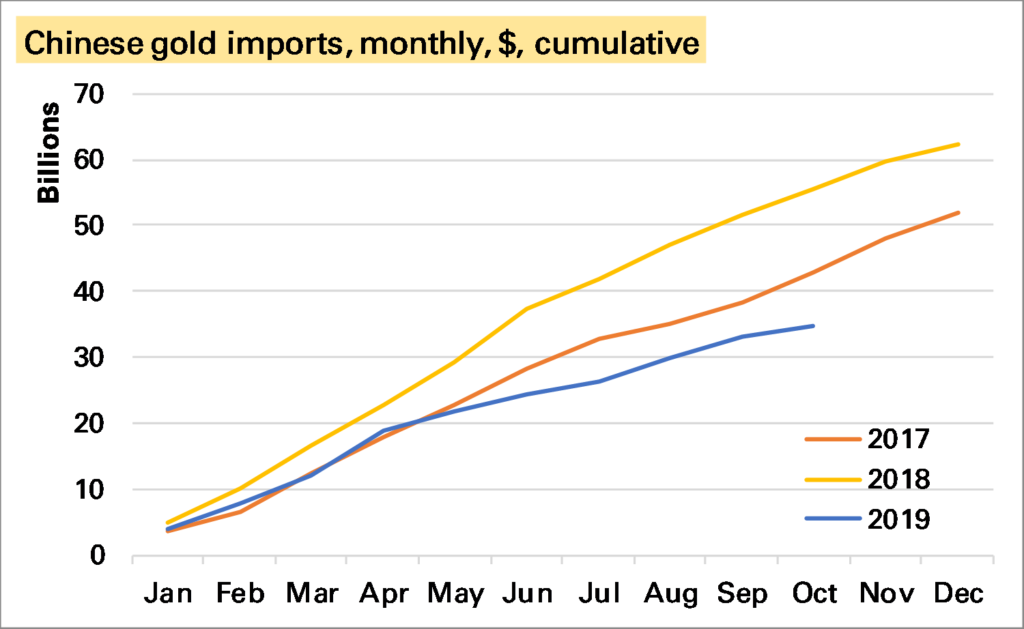

The high gold price is another factor. The first chart below shows that imports in the last two months have been made at by far the highest price in this data series, and arguably are not out of line with previous trends. In terms of the amount of money spent on imports the trend does not look as poor as for the volume (second chart below) though October was still a poor month.

Year-to-date gold imports are now around 800t, well below the levels seen in the last two years. In terms of money spent the gap is narrower – and perhaps not too bad given the restrictions placed on imports earlier in the year – though again October does stand out as suggesting a worse trend.

Source: All charts – China Customs. Note click on chart to enlarge.

To what extent does this matter? It’s possible China is importing gold in other forms such as jewellery, or there are more unofficial imports going in. Even if not (Western) investors have been buying a lot of gold, and despite all the talk of gold stockpiles, this tends to mean the Chinese can’t have as much. The price rises to see who wants it most and typically it’s the investors.

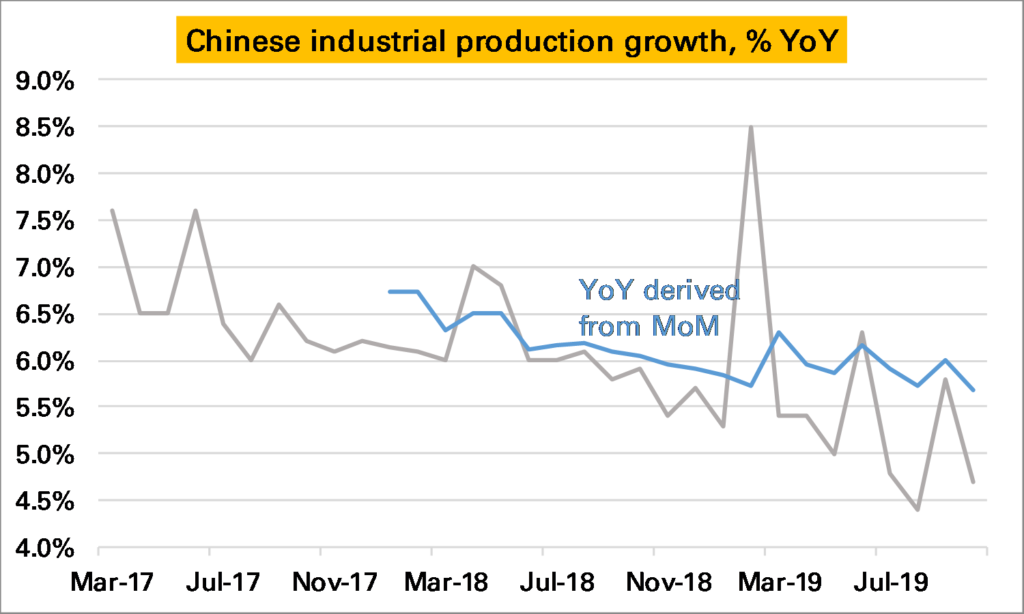

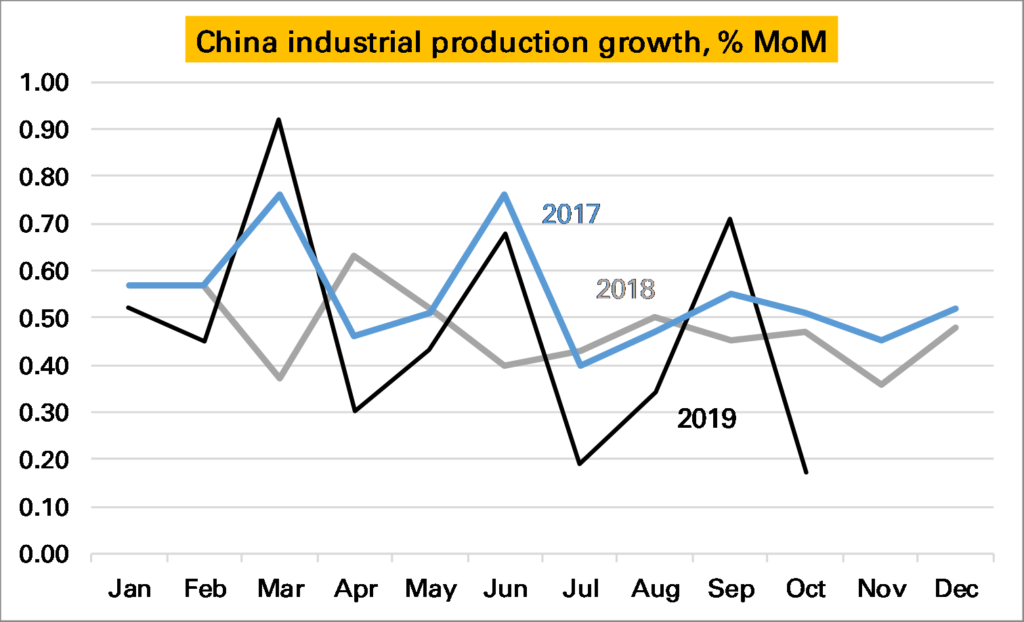

But… the biggest risk to the gold market medium-term, in my view, is lacklustre”physical” demand, of which over 50% comes from China and India. In particular it seems to me that gold – both as a consumer good and an investment good – now faces far more competitors (eg smartphones, index-linked bonds) than it once did. Of course some of its qualities are unique and it has a long track-record, suggesting a certain robustness.

That the dollar spend on Chinese gold imports is declining could be another warning sign.

For the background on how China now publishes gold trade data see my LBMA Alchemist piece from earlier this year.